30 March 1984

Introduction

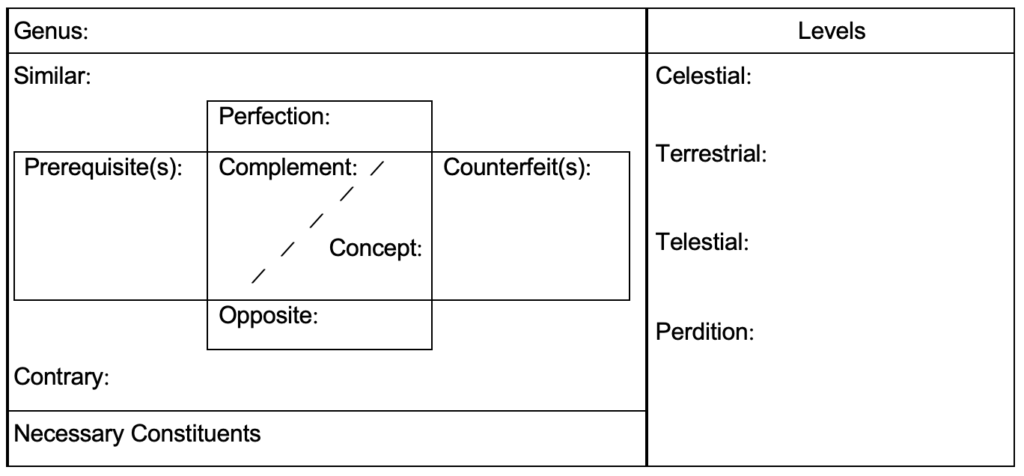

This taxonomy is a structure of concepts which is intended to serve as a directory of the basic processes of the human intellect. In the account which follows there is an attempt to provide sufficient description of each element of the taxonomy so that the reader may understand the principles which individuate each element as well as the structure of identities which relate them to each other. It is hoped that the taxonomy is sufficiently exhaustive and definitive to be useful for many purposes.

The main divisions of human intellectual process are assumed to be three in number, corresponding to the human functions of willing, thinking and acting. The most fundamental of these categories is here taken to be the volitional, that process by which a human being expresses his desires. Volition is taken to be the independent variable in the human system. The second category is that of thinking, the processes by which the will creates and manipulates ideas. Thinking is divided into three main areas: imagination, basic thinking and advanced thinking. The third category of intellectual processes is that of acting, corresponding to the volitional body functions of the human being. Fundamental to this work is the assumption that the human being is always functioning in all three ways when conscious: willing, thinking and acting are always in process in the human being, and always as a triad. Though acting may be suppressed at times, it is here assumed that the impulse to act is always part of any willing-thinking process.

To facilitate understanding of this taxonomy, two separate devices are employed. This first is a one-page summary (the last page of this work), frequent reference to which may assist the reader to grasp the gestalt of the taxonomy. The second is a narrative description of the categories and subcategories which is intended to provide detail and to suggest other interrelationships not immediately apparent on the one-page summary.

Imagination: The creation of concept patterns in the mind.

Imagination is here seen as the process of forming ideas. The general term “idea” will seldom be used in this work because of its ambiguity. The notion of concept will be employed in its place. To the term concept are attributed the following properties:

- There is an image, form or structure associated with each concept.

- Concepts are creative constructions of the human mind.

- There is an essentially infinite number of variations of concepts possible.

- Concepts may be elemental or of a complexity exceeding that of the universe.

We begin with imagination because of the fundamental role which concepts are seen to play in mentation. While the Lockean apparatus of tabula rasa is not here assumed, it does seem apparent that the human mind is first stimulated largely by sensation and that as sensations are repeated and become familiar, they become the occasion of perception.

Perception is defined as the identification of a present sensation as something familiar, something which previous experience has stimulated the mind to coalesce into at least a rudimentary concept. Perception seems to begin as a reflexive and automatic human activity. It also seems to eventuate in a process which may be deliberately and creatively controlled by an intelligent adult. For the adult, perception seems to be the conscious assignment of a sensation to a concept more or less also consciously shaped in previous mentation. Perception is thus recognition.

The raw material of perception is always sensation. That sensation may be painful, pleasurable or simply informational. It may come through any sensory mechanism, of which at least twenty-five have been identified in the human body. Attention may focus on a sensation according to the will of the person, or may be ignored as are the overwhelming number of daily sensations. There is for each individual a pain/pleasure threshold which when exceeded, supervenes into the consciousness and cannot be ignored. But no sensation is self-interpreting, self-meaningful. For sensation to become perception it must be received into the concept matrix.

Conception is the process of forming types or categories in the imagination. Every concept is a general notion. Perception seems to be the basis of the initial concepts one has, yet we do not seem to perceive until we have concepts into which to receive and by which to interpret sense data.

The question of the possibility of inherent concepts is pertinent. It does seem that there are some universal or nearly universal concepts or concept relations, such as up-good and down-bad. The presence of such universal patterns does not necessitate the conclusion that concept patterns are neurologically inherited, but it does cause us to take the question seriously.

In all of the intellectual process hereafter described, concept is taken to be the basic unit of intellection, the sine qua non of intellectual process. Two generalizations are asserted:

- All human mental life is a processing of concepts.

- Concepts replace percepts as soon as possible and wherever possible.

The evidence for the latter generalization is found in each person. Concept is the realm of power, control, familiarity, and creativity. Percept is the area of the unknown, of danger, of challenge, of effort. To prefer concept over precept when given a choice is for most persons simply the path of least effort and least challenge, as is the basis of the unwillingness to learn observed in many persons.

Volition: The exercise of will in creating and using concepts.

The first category of volition is that of imagination, that is treated in the previous section. Imagination came before volition in this taxonomy because a concept base is necessary before the human will can operate. This is to say, there must be alternatives before any choosing can be done. Imagination is placed as the first category under volition to emphasize that ultimately both the concepts and the percepts one entertains are very much under his control. That control is total for concepts and begins to approach totality for percepts according to the degree of power or control one has over his physical environment.

Attending, the second category under volition, is the process of focusing the attention on one rather than other concepts (including percepts). Most attending is a function of will, the exception being that noted above of physically overwhelming percepts. In a perceptual situation, the number of foci options may be as high as 1×105 for each separate moment. This number registers the number of sensorily discriminable particulars upon which attention could potentially focus in any natural setting such as a forest landscape. The number of potential foci for conception at any given moment is usually far greater than in the perceptual realm. Were it not for the ability to focus attention, we probably would drown mentally under the overwhelming magnitude of the number of concepts in our mental system which would crowd our consciousness.

Preferring is the third item under volition. To prefer is to select one concept over another or others for some use such as contemplation or action. To prefer is different from attending in that whereas attending to a series of concepts means to examine each one successively, preferring is to take one of that series and judge it to be the best for a use or activity which is then initiated. For example, we have a concept we wish to express in a line of poetry. We have at our command a series of (concepts of) symbols which are candidates to represent what we wish to say in the poem. We first successively attend to a paired comparison of the concept which we wish to express with each symbol of the representational series. Then we prefer the one which we feel best expresses what we wish to say while meeting the formal requirements of meter, rhyme, etc., in the code sequence (poem line) which we are building.

Choosing, the fourth of volition, is similar to preferring in that we first attend to a series of concepts (at least two items) and then select one for action. It is differentiated from preferring in that candidates for choosing are here always concepts which are percepts (concepts having an immediate sensory matching correlate), while preferring is always an operation upon a series of non-perceived (at the moment) concepts. Thus concepts which have no physical referent or correlative can only be preferred, while those which may have a referent is sensorily present. The reason for employing this distinction between preferring and choosing is that when we prefer, we always know exactly what it is that we are selecting because we control our own concepts completely. This is knowing one’s own mind. But in choosing we are always selecting a referent in the external world as a focus for physical action. We choose what we think we know because of the concept we have which makes perception of that referent possible; but we never know referents in the real world so thoroughly that we never run any risk. This is to say that our concept of the referent is never the exact counterpart of the referent. Therefore choosing involves a risk of dealing with the unknown which preferring does not.

The fifth type of volition is remembering. Remembering is preferring retrieval links which then serve as tethers for concepts which we wish to be able to recall at will. When ideas are attended to which are very interesting to the person, remembering links are formed automatically. But a person can remember anything he wishes to be able to recall at will, interesting or not, by the deliberate formation of retrieval links. This conscious remembering is a key factor in learning, which is discussed below.

Recalling is the sixth volitional intellectual process. Recall is to employ the retrieval links formed in remembering and to bring to the focus of attention some desired concept which is not there. In computer language, to remember is to “save” and to recall is to “load”.

The seventh process is that of forgetting. Since the human mind does not erase in the same manner as one can erase memory in a computer, forgetting takes the form of neglecting to form retrieval links or of interest or deliberate remembering. Forgetting is a defense mechanism. If we could not forget anything, then our retrieval links would often bring back more than we care to recall. Sometimes we desire not to be responsible for doing something, so we deliberately forget. Since folklore has it that we cannot be held responsible for that which we have forgotten, forgetting becomes a basis for self-justification. The view here maintained is that all forgetting is deliberate, and act of preference. That preferring may be active, a deliberate blocking, or passive, not forming retrieval links, but is nevertheless in the arena of preference in either case.

The eighth volitional process is that of feeling. Feeling is an emotional state. We assume here faute de mieux that an emotional state is at least in part an endocrine reaction of the human body. But it is also assumed that the power to generate and to negate such emotional states is entirely within the volitional power of any person who wishes to gain that control. Many persons succumb to the folklore that feeling is something that “happens” to a person, for which he is not responsible. The refutation of that latter position is found in the persons who seek and gain total control over their emotional states. Naturally those who have control are more positive witnesses for the volitional position than those who do not have control of their emotions.

The ninth volitional intellectual process is that of thinking. Thinking is defined as the creating and processing of concepts. Thus thinking is a generic term which covers all intellectual processes. It is mentioned here as part of a triad: feeling, thinking and acting, which triad are the three things which human beings do. Preferring is here seen as the fundamental mode of thinking. As we prefer, we think, then feel, then act.

Tenth and final in the volitional processes is then the category of acting. Acting is an intellectual process because it is learned and controlled through concepts. The forming and implementing of action sequences is a process in which the mind plays a pivotal role. The major forms of action will be discussed below, though not in the detail with which thinking is dealt with.

Basic Thinking: The relating of concepts.

Assertion is the initial type of basic thinking. It is the combining of two or more concepts by means of an appropriate copula and with sufficient quantification that we are making a statement about something. Traditional usage has called this type of formulation a “proposition”; that terminology is not used here because of unwanted connotations. Assertions, like meanings exist only in the mind, and are meaning complexes. When encoded they are represented by sentences. We communicate sentences, but the assertion intended by the encoder and the assertion created by the decoder always exist in the private province of the mind; we have no means of knowing that the two ever are identical. An example of a sentence which represents an assertion is to take the symbols “characteristic”, “color”, “green” and “chlorophyl” and combine them: “The characteristic color of chlorophyl is green.” Such statements may then be used as premises.

Identification is the second process of basic thinking. It is preferring to treat two concepts as if they were the same. Sameness is a matter of degree, so identification may be merely the assertion of vague similarity, or it might range to the assertion of absolute one-to-one correspondence. Whether we identify two concepts as being identical or not depends upon the use which we wish to make of them. For purposes of housing, clothing and transporting we identify the different manifestations of one of our children as being the same person; but for purposes of nourishment, discipline and encouragement it pays to take the manifestations of that same child as being a slightly different person in each case.

Supposing two concepts to be different is the third type of basic thinking. We shall call this the process of individuating. It is the complement of the process of individuating. It is the complement of the process of identifying, and the two are nearly always used in conjunction with each other, much as one always uses the two blades of a scissors together to do the cutting that is desired. Individuation is a matter of preference and of degree just as is identification.

Deduction is the fourth representative of the category of basic thinking. Deduction is defined as the deriving of necessary conclusions from given premises in accordance with given rules. The rules specify what parameters the premises must contain and the sequence of inference involved. For example, the rules of the categorical syllogism are the definitions of the terms involved (middle, major, minor, distribution, quality and quantity) and the five rules which govern distribution, quality and quantity.

The fifth type of basic thinking is induction, which is preferring to identify the concept which represents the sample of some population as a sufficient concept to represent the whole of that population. Thus if we perceive a line segment to be straight; or if a person has dealt with us honestly in the past that he will also deal honestly in the future. We also sometimes assume that a thing which we perceive to exist at one time and then again at a later time also continued to exist even at those times in between our observations when we did not perceive it. Thus by extrapolation and interpolation we fill in the blanks in our concept of existence created by the interstices related to our perceptual experience.

Adduction is the sixth type, and is defined as the process of supplying premises from which a given conclusion may validly be deduced. When we theorize or explain, we are usually adducing. There are always an infinite number of potential premises which logically satisfy the need to adduce, which is why we are seldom at a loss when the need arises to explain or to justify something. Adduction is the proper opposite to deduction rather than induction, which is sometimes mistakenly given that role.

The seventh category of basic thinking process is analysis, which is the task of breaking the concept down into constituent parts. Some concepts are simple and cannot be analyzed, but most are complex and can be processed by this means. Analysis may be partial or exhaustive, and the mode of analysis will vary according to the purpose the analyzer has in mind. For example, a soil may be analyzed for its chemical composition, and each can be done to designate the major constituents only or can be exhaustive, and the mode of analysis will vary according to the purpose the analyzer has in mind. For example, a soil may be analyzed as to its physical particles (sand, silt, clays) or it can be analyzed for its chemical composition, and each can be done to designate the major constituents only or can be exhaustive. The elements of a complex concept may be percepts when discovered, but always function as concepts in the part-to-part and part-to-whole relationships which it is the purpose of analysis to establish.

Abstraction is the eighth type of basic thinking. It takes the products of analysis and attends to one or more of them, ignoring the remainder of the constituents. Abstraction is purposive, creative and arbitrary. We abstract plots from novels, patterns of worship from cultures, essences from wholes. In the manner of speaking here employed, abstraction is always a conceptual process. When we perform this process in a perceptual realm by a physical operation, we speak of extraction rather than abstraction. Abstraction is a specialized form of attending.

The final and ninth type of basic thinking designated here is that of naming. Naming is the process of relating a concept to another which has a physical counterpart which serves as a symbol. Naming is the joining of two concepts in the mind, such as the number which comes after six and the idea of seven. We do this so that we may refer to the number which comes after six by the word “seven,” supposing seven to be the counterpart of “seven.” The question always is, is not the number which comes after six nothing but seven? At any rate, we use “seven” to represent seven, and thus have named at least it, and perhaps we may assume identity between seven and the number which comes after six.

Admitting that the line which separates basic thinking from advanced thinking is perhaps more one of accident than essence, we now proceed to examine those more complex combinations of thinking processes.

Advanced thinking: Creating/processing concepts in a learned sequence.

The first type of advanced thinking is that of learning. Learning finds its ancestry in remembering, which in turn traces back to preferring. We learn that which we wish to learn. Learning is preferring thinking/feeling/acting sequences until they are habitual. The desired state of learning important things is that they be “over-learned,” learned so well that once the habit is triggered one need not think about how the sequence is executed. One knows it so well that it is performed automatically. There is an inherent capacity in human beings to learn which is manifest differentially. Some excel in languages, others in controlling their emotions, others in physical skills. While nearly everyone can master the rudiments of most activities, that is to say, learn something about nearly anything that can be learned, the learning attainments of humans vary vastly both because of desire and because of differential talent. A factor of learning often not in the person’s control is that which is available to be learned. Nevertheless, it is a good maxim that any person with sufficient desire can learn virtually anything he can conceive of learning.

The second category of advanced thinking is that of taxonomizing, which is the creation of systems of categories having an internal structure which relates the associated categories in some logical or useful manner. Thus we create taxonomies of foods so that we may have understanding of what is offered to us and that which we might choose to fulfill the desire to nourish ourselves. We create taxonomies of people out of things we have learned about individuals and types of persons we have met. We acquire taxonomies with the language we learn, finding ready-made systems of persons, places and things which we then amend through our own experience and creativity. Creativity itself is taxonomizing, the invention of concept systems to satisfy some need. The concept we have in our minds of the reality of the physical universe is a taxonomy which we have partly been given and have partly created. The whole of the future of the universe or any of its parts is an additional but closely related taxonomy, as is our idea of the past. Virtually every intellectual endeavor we engage in involves either the creation or use of taxonomies, or both. Integral to these taxonomies are the laws and theories we have about everything. When we take a trip in our minds, we move from category to category withing our taxonomy of geography. When we mentally invent a new way to skin a cat, we are creating are creating a new taxonomy of action process. When we play a piece on the piano, we are following a taxonomy created by the composer of the piece, and the rendition we created is itself a taxonomy of sounds and relationships of sounds. Every language is a taxonomy of symbols; its grammatical rules are the generalizations about the categories of symbols and symbol associations. We use taxonomies whenever we identify anything or use anything or think of anything in relation to the things which are like it. Indeed, all thinking processes are related into a whole by the process of taxonomizing. Taxonomies are concept systems, and every system-concept is a taxonomy.

The third type of advanced thinking is that of comprehending, which is contemplating a concept in a nexus of related concepts. We shall subdivide comprehending into knowing, understanding, measuring and judging, and treat each of those subtypes separately.

Knowing is defined as perceiving something thoroughly using many related percepts and concepts. Thus when we desire to know something we examine it very carefully, taking many perceptual “shots” or pictures of it through every sensory mechanism which is appropriate to the circumstance. While gaining this mass of observations we are comparing what we sense with other things previously experienced, and make decisions about sameness and difference. We try to guess what it will do next or be next, what produced it, etc. When our observations seem to bring nothing new and our questions are satisfied, we then say we know. Knowledge is a relative thing, for the familiarity which allows one person to say he knows might be only the beginning of an investigation for another person. Sure knowledge is perhaps a thing which eludes human beings; we seem to approach it only asymptotically. We cannot be sure because our observations and understandings of anything are always theory-laden in that we assume things we do not and cannot know to be true in the process of gaining the familiarity which enables us to say that we know. Knowledge is thus a common-sense category, not having social standardization or precision. Science would claim to be that standardization, but it has not been accepted as such by the majority of human beings as yet.

Understanding is the process of contemplating a concept in relation to the other concepts with which it is most closely related. We understand things by before and after, by cause and effect, by desire and action, all being general complexes by which we develop the ability to relate other concepts to the one we wish to more fully comprehend. Understanding need not be vertical. Supposing one understands when one does not is still understanding, however lamentable and misleading that may be. Like knowing, understanding is a matter of degree. Complete, true understanding is a thing which we also approach only asymptotically.

Measuring is identifying a percept or concept with one of the standard series. By “standard” is meant a set of differentiations which are in common use in a society, such as the metric system, color designations, monetary units, etc. If we are dealing with a perceived piece of lumber, we measure it against the standards which have been set for the lumber. If we are not skilled, we will need to measure the dimensions of the piece to determine that it is a 2×4 and not a 2×6. If we are skilled, we simply measure the perception of the piece against the concept array we have in our minds and designate its dimensions. When we attempt to measure that which is only a concept, not a percept, the matter becomes less sure because we cannot now resort to physical measurement as a backup to mental measurement. For instance, there is no physical test which we can use to determine if person X is an honest man. We have in our minds a series which extends perhaps from being painfully honest to being a pathological liar. Any measurement we make depends upon first abstracting from a great many experiences with person X the typical action he performs, then we identify that typical action with some member of the honesty series. Needless to say, mental measurements may indeed be accurate but tend to be more subjective than do physical measurements, which is the reason scientists insist upon physical measurements. Mental measurement falls in the realm of common sense, uncommon though it often is.

Judging is the identifying of a percept or concept with satisfaction or non-satisfaction of preferred criteria. The criteria involved might be single or very complex, public or private. We might judge whether or not we have enough gasoline in our tank after measuring it. Or we might judge whether the automobile we drive is satisfactory or not, taking many factors into account. We may judge that an election was fair according to the legally established requirements, or we might judge that the election fully satisfied our own personal preferences. One judgment we often attempt but also often fail at is judging whether or not something will satisfy the personal preferences of another person. We are experts on our own preferences, since we each create our own, but we are all guessers at envisioning just what will satisfy others. Successful guessers in this area of judgment have a special advantage in love, war, business and politics.

Comprehending is constituted, then, of these four special activities: careful perception, correlation with related concepts, identification with members of standard series of concepts, and identification with satisfaction or nonsatisfaction of preference. These constitute the qualitative, effective, quantitative and purposive aspects of understanding, which may roughly be correlated with the four factors of formal, efficient, material and final causes in the taxonomy of comprehending proposed by Aristotle.

The next and fourth area of advanced thinking is that of translating, which will be subdivided into encoding and decoding. Translation is the enterprise of relating codes to concepts and has the two main types which will be explicated.

Encoding is choosing a code sequence to represent a concept sequence. It is the formulation of a message. A message is a code sequence created to represent an assertion or set of assertions in the mind of a sender. The essential factors which the sender must consider in encoding are the language(s) familiar to the intended receiver, the codes familiar to the receiver, and the understanding or worldview of the receiver. Language controls the possible interpretations which may be made by the receiver. Usually the speaker or sender must guess at the precise nature of all three of these factors for a given target person. Again, good guessers are favored. Good guessers usually have made a preliminary test of the situation by experimenting with trivial messages to determine reaction, proceeding with progressively more complex and/or more important messages until the sender’s purpose is fulfilled or confusion in the mind of the receiver is irresolvable (which is failure of translation).

Decoding is the creation of a concept sequence to represent a given code sequence. The receiver must make some assumptions about the speaker such as the speaker’s purpose, language, main assertion, understanding, and the relevance of what is said. Each assumption must remain a guess, but can be an educated guess if the receiver has had previous experience and/or communication with the sender. The receiver must decode each code sequence into an assertion, then must abstract the principal thrust of the message and make judgments as to just how important, veridical, useful and representative that message is.

Since neither encoding nor decoding is an exact process, the business of translation is always experimental. For an enterprise which is not in control we do remarkably well, but the part of wisdom no doubt is always to remember the fallibility of the process.

The fifth process of advanced thinking is that of scholarship. This process has been created because there are many things of interest to human beings which cannot be known (perceived surely or even at all), such as the past. Scholarship is the process of fabricating a reasonable account of something not now perceived (such as the past) by taking accounts of the past, preferably those created at the time by an eye witnesses of the past event which they depict (primary sources) or those created at some other time and means by someone else (secondary sources), adding information from scientific study of objects now present which were also present in the past event, then creating a taxonomy of actors, causes, events and outcomes to satisfy the questions which one might reasonably ask about the past. Such a process is always guesswork, but they are educated guesses and uneducated ones. An educated guess may prove in the light of evidence discovered later to be good or bad, as may educated guesses; but the preponderance of experience is that educated guesses are more often vindicated than are their uneducated counterparts such as hearsay, tale and supposition.

The sixth process in this area is science. Whereas scholarship has the problem of fabricating reliable accounts about that which is not now observed, science is the process of fabricating reliable accounts about what we do observe. Science has several separate tasks. First, to produce reliable identifications of presently sensed objects and events with established taxonomies of the objects and events of the world: this is the enterprise of establishing scientific facts. Secondly, there is need to abstract from collections of facts certain features which can then be inductively established as the typical objects and events which can serve as reliable bases for accurate prediction of future observations. It may be seen as the creation of taxonomies. Thirdly, there is need to create general accounts of how object and events relate to and are explained by things which are not observable, such as the past, the future, the very large, the very small, etc. such accounts are known as theory, or visions of the whole, which consist of a taxonomy of concepts, part of which are imaginary, part of which correlate with past and with predicted observations, and all of which form a rational (consistent) whole.

There are special criteria which govern the acceptability of assertions about scientific facts, laws and theories. These form a series which is time related, beginning with the need to be self-consistent and lately adding the requirement to be entirely naturalistic. The specifics of these culture related aspects of science must be treated elsewhere. It is sufficient to note that they are definite strictures within which the enterprise of scientific thinking must operate.

The seventh form of advanced thinking is philosophy. Philosophy is the process of creating intellectual processes for solving intellectual problems and the processing of intellectual problems for which no standard process has been established. For example, science is the child of philosophy, created out of the need to have definitive, reliable information about the world. As philosophy has found ways to deal with successive subject matters which are definitive and reliable, such areas have successively moved from the domain of philosophy to the domain of science. Psychology did this at the beginning of the twentieth century; linguistics moved at mid-century. The leftover problems which do not admit of ready and systematic solution remain in the province of philosophy. Philosophy is thus the domain of trying to answer the most difficult and enduring questions which human beings have learned to ask.

Religion is the eighth and final form of advanced thinking. This endeavor is the conscious and deliberate task of creating and maintaining one’s personal habits of thinking/feeling/acting in accordance with one’s educated preferences. And educated preference is one relative to which a person has had sufficient experience to know what sort of thing it is that he desires, or he has sufficient understanding of something that his choices are at least rational within the options he understands. Religion is the enterprise of character building, which is always a do-it-yourself project. It operates by judging satisfaction or dissatisfaction with present habits and the satisfactions which their implementation yields. When one is dissatisfied, one searches out a new possibility for thinking/feeling/acting and implements it. If the result is so gratifying that the person is satisfied, then the person deliberately learns this behavior. When the behavior is learned, its implementation is triggered by some stimulus or consciously produced signal. The person thereafter enjoys the ability to do that thing and to receive the rewards which flow from it as long as his preferences remain the same and as long as the environment which returns the satisfaction he desires continues to deliver that fulfillment which he so cherishes. Dissatisfaction is thus the root of religious conversion or change, and satisfaction is the root of religious observance of what one has learned to think/feel/do.

There are a great many other candidates for inclusion in the category of advanced thinking. The supposition here maintained is that the present taxonomy contains all of those candidates as subdivisions of the present taxonomy.

Acting: Preferring is to carry out through one’s body a learned concept sequence. (Also known as art and as communication.)

A person acts to make a difference, to have an effect upon his environment, ostensibly to change it so that it will afford him satisfactions which he deems will not be forthcoming otherwise. This acting with deliberate intent is art, the process of art. This art may be artless, that is to say unskilled, but yet be art because of the deliberate intent. Since artless art seldom is satisfying, persons learn to become skilled at doing what they do so that they will gain the fulfillment of their desires.

This art or acting may also be termed communication under the definition that to communicate with something is to affect it. All acting is done to affect something, as is all artistic processing, as is all communicating. These broad definitions or art and communication enable us to identify three things that are essentially the same but are not seen so to be in the minds of many people.

We shall divide the general category of act into only two main types, those of acting through codes and those of acting through physical force.

Action through the use of physical force we shall call technology. The development of effective sequences of the application of force is a creative activity which falls under the head of taxonomizing. The process of tanning a hide, for instance, is a series of steps which must be carefully laid out in proper sequence with proper quality control and action alternatives at each step. To create this action sequence in the mind is the task of taxonomy; to assure its perpetuity is to learn it; to perform it well is to acquire the thinking/feeling/acting habits which enable one to succeed in actual performance, which is religion; to trigger the action sequence to perform at a specific time and place on specific material is technology.

There is a multitude of technology patterns which human beings employ. Employment of each is an intellectual process because one must carefully measure the environment to determine the exact time, place and expenditure of effort which will achieve the desired end. Technology requires coordinated use of many if not most of the intellectual processes of this taxonomy.

The second general category of acting is that of code communication, which is the delivery of encoded messages. This form of acting may also be called a technology in the parlance of general usage, but not so in this taxonomy, for here technology is limited to those communications which involve some application of physical force, a discernable push which derives from muscular effort, as in the driving of a nail or the flipping of a switch.

Code communication is almost always multichannelled; it is the employment of two or more codes at once. Thus a person says one thing with his words, sends a contrary message by his body motions, and may demonstrate a third message by the pattern of his subsequent choices. Paying attention to all of the encodations involved is to focus on total communication, as contrasted with simple attention paid to a person’s words.

Because of its importance, we shall subdivide code communication into three subcategories and elaborate upon each of them.

The first subcategory of coded communication is disclosure. Disclosure is the sending of messages relative to one’s feelings, beliefs, and desires. In general, this is the domain of all of those things internal to a person which can only be understood if the person himself discloses them, hence the name. Besides the usual problem of interpreting the code correctly, disclosure adds the special burden of often being incorrect, not being a true reflection of how a person really feels. This is sometimes true even when the person honestly desires to tell what is going on inside himself.

The second subcategory is that of directive. Directive is communication of commands with the intent of causing action on the part of others who receive the encodation. Other examples of this type of discourse are questions, definitions and art forms of the so-called “fine arts,” each of which is designed both to command attention and to cause some action in the thinking/feeling/ acting syndromes of the person receiving the communication.

The third subcategory is that of description. A description is an assertion which purports to convey to the hearer the actual state of the reality of something in the universe. Its purpose is not only to inform but to command assent. Included in this type are four main divisions which correspond to the divisions of scientific discourse: factual assertions (the identification of a present sensory phenomenon relative to an established taxonomy); law assertions (the establishment of reliable inductive generalizations about the facts which have been observed); theoretical assertions (the hypothesizing of creative fictions to account for the laws and facts which have been established in an area of thought); and principles, (which are the initial and unprovable premises upon which the hypothesizing of theorization builds).

(We note in passing that there are two basic uses of coded communication. The first is to transmit information to a person while doing the utmost possible not to coerce that person. This will here be called persuasion. Persuasion is limited to disclosure code assertions. The second mode of coded communication is to attempt to coerce the hearer. This is done by issuing directives or descriptions as if one had authority to do so. Speaking as if one has authority we shall denominate as “dominion.” If one truly has authority, then the use of dominion seems appropriate. We also note in passing that virtually all of the authority known in this world comes by the use of technology, the deliberate employment of physical force. The development of networks of technology by which to gain dominion over other people seems to be the principle preference of many human beings, the search for money, class, title and certification being witness to this artful enterprise.)

The taxonomy of intellectual processes is thus complete. The taxonomy is useful if it enables a person to expand his understanding of the whole and/or the parts of the intellectual processes employed by mankind. The taxonomy is valid if it truly represents all of the processes so employed and if it so subdivides them in a manner which facilitates identification, description and the use of the processes without doing violence to any of them by forcing them into categories where they have unlike companion categories.

The Taxonomy of Intellectual Processes

Imagination: The creation of concept patterns in the mind.

- Perception: Use of immediate sensation to create a concept pattern.

- Conception: Creation of new concepts by recombination of old ones.

Volition: The exercise of will in creating and using concepts.

- Imagination: The creation of concept patterns in the mind.

- Attending: Focus of consciousness on a concept or concept complex.

- Preferring: Selection of one concept over another.

- Choosing: Selection of one percept over another.

- Remembering: Preferring retrieval links to bring concepts to focus.

- Recalling: Preferring retrieval links to bring concepts into focus.

- Forgetting: Erasing or blocking of retrieval links.

- Feeling: Generation of and dwelling in an emotional state.

- Thinking: Creation and processing of concepts.

- Acting: Preferring to carry out in one’s body a learned concept sequence.

Basic thinking: The relating of concepts.

- Assertion: Combining two or more concepts into a statement or premise.

- Identification: Asserting that two concept patterns are alike.

- Individuation: Asserting that two concept patterns are different.

- Deduction: Drawing necessary conclusions from given premises.

- Induction: Assuming the whole to be like the part.

- Adduction: Supplying premises for a given conclusion.

- Analysis: Breaking a concept into its constituent concepts.

- Abstraction: Focus on some constituent concepts, ignoring the remainder.

- Naming: Assigning a code to represent a concept.

Advanced thinking: Creating/processing concepts in a learned sequence.

- Learning: Preferring thinking/feeling/acting/ sequences until habitual.

- Taxonomizing: Creation of concept systems.

- Comprehending: Contemplating a concept in a nexus of related concepts.

- Knowing: Perceive thoroughly using many related percepts and concepts.

- Understanding: Focus on a concept in the nexus of related concepts.

- Measuring: Identifying a percept/concept with one of a standard series.

- Judging: Identifying a percept/concept with one of a preferred series.

- Translating: Relating codes to concepts.

- Encoding: Choosing a code sequence to represent a concept sequence.

- Decoding: Creating a concept sequence to represent a code sequence.

Scholarship: Encoding a creative synthesis of one’s decodings.

Science: Encoding a creative synthesis of decodings and percepts/concepts.

Philosophy: Creation of intellectual processes and processing of problems.

Religion: Creating/maintaining personal habits of thinking/feeling/acting.

Acting: Preferring to carry out in one’s body a learned concept sequence.

(Also known as: art, communication.)

- Technology: Use of physical force to affect one’s environment.

- Coded communication: Delivery to another of an encoded assertion.

- Disclosure: Communication of one’s feelings, beliefs or desires.

- Directive: Communication of commands to cause action.

- Description: Communication of assertions to control belief in others.